The increase in the provincial minimum wage (UMP) in 2026 must be balanced with an increase in productivity levels to maintain business sustainability and investment climate prospects, according to a study released by the Asian Productivity Organization (APO), a non-profit organization based in Tokyo, Japan.

The latest APO Productivity Readiness 2025 report reveals that a country's standard of living is highly dependent on its productivity.

"High productivity will increase per capita income, which will then enable the country to improve social welfare and environmental quality," according to the report.

However, this report shows that there is a large gap between high-income countries and middle- and low-income countries. Countries such as Singapore and Japan have productivity levels that far exceed low-income countries such as Bangladesh.

The data shows that Singapore ranks highest with a Productivity Readiness Index (PRI) of 98 in 2022. Hong Kong follows with an index of 88, and Japan (84). Meanwhile, South Korea has a score of 76.

Upper-middle-income countries such as Malaysia have an index of 69, Thailand (56). Meanwhile, Indonesia has an index of 50, which is below average. Lower-middle-income countries such as Sri Lanka have an index of (35) and Cambodia (36).

Indonesia ranks 13th out of 21 APO member countries, or fourth in Southeast Asia after Singapore, Malaysia, and Thailand, slightly above the Philippines and Vietnam.

Cheap Labor

According to Senior Economist at the Institute for Development of Economics and Finance (INDEF), Tauhid Ahmad, Indonesia is often positioned regionally as a country with competitive labor costs. However, this advantage has become a long-term trap.

"We have relied on cheap labor for too long. As a result, investment in education and improving the quality of human resources has stagnated. When industry needs higher technology, the workforce is not ready to keep up. Ultimately, productivity does not increase," he told SUAR.

Tauhid said the problem is structural. First, the quality of education and training does not fully meet the needs of industry. Second, the industrial structure still relies on labor-intensive, low-tech sectors.

"If wages continue to be suppressed, companies will tend to hire more low-cost workers rather than invest in technology," said Tauhid.

In the long term, this backfires; productivity is low, wages are difficult to increase, and workers are easily replaced.

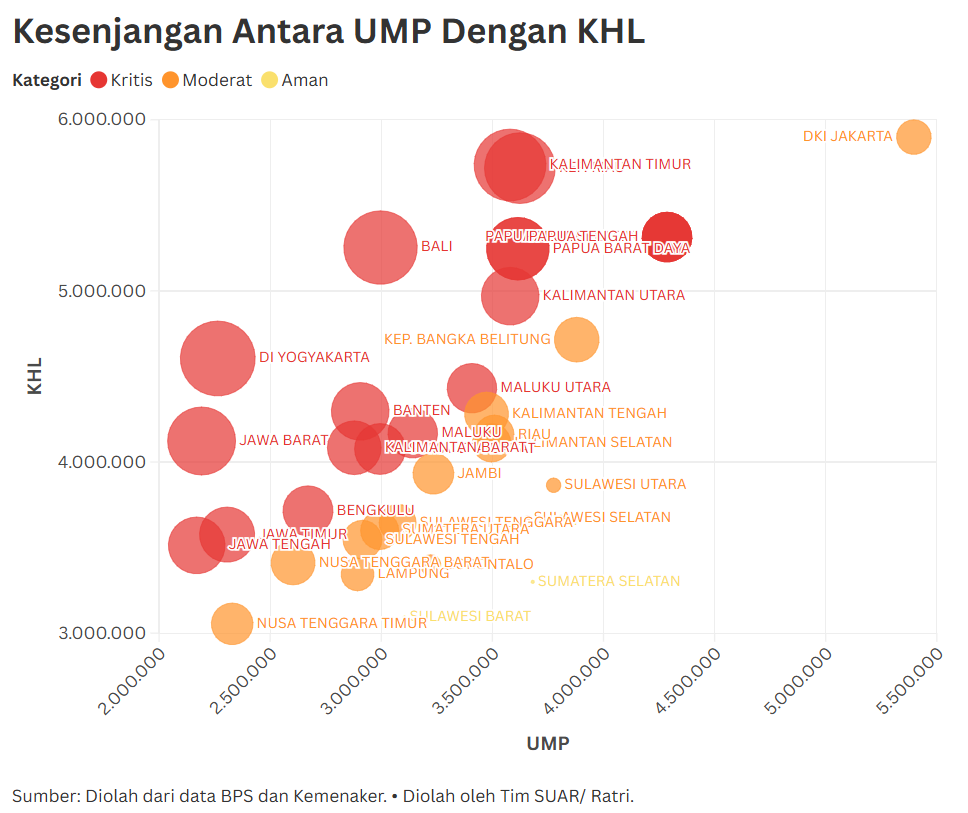

In the report on the State of Workers in Indonesia and the State of the Labor Force in Indonesia launched in December 2025, the Central Statistics Agency noted that with an average working time of 41 hours per week, the average monthly net income of workers in Indonesia currently stands at Rp3,005,200, an increase from Rp2,963,400 in August 2024.

The three highest-paying sectors are information and communications (Rp5.16 million), finance and insurance (Rp5.09 million), and electricity, gas, hot air/cold air supply (Rp4.95 million). Meanwhile, the three provinces with the highest monthly net salaries are DKI Jakarta (IDR 5.90 million), Central Papua (IDR 4.81 million), and Riau Islands (IDR 4.77 million).

Based on education level, the average net income range for workers with a high school diploma or higher is currently between Rp3,149,687 and Rp4,804,860 per month, while the average net income for workers with a junior high school diploma or lower ranges from Rp2,083,427 to Rp2,482,817.

In terms of aggregate population, out of 70,816,265 registered workers, 40,166,024 workers earned a net income above Rp2,000,000, while based on the provincial minimum wage benchmark, only 50.3% of workers in Indonesia earned a salary above the UMP in August 2025.

In other words, 5 out of 10 workers in Indonesia currently still earn wages below the minimum wage," according to the BPS report.

Among the sectors that support national economic growth, workers in the manufacturing sector have an average monthly income of Rp4,545,388, with 43 working hours per week. Meanwhile, workers in the wholesale and retail trade sector earn an average income of Rp2,704,788 with 46 working hours per week, while workers in the agriculture, forestry, and fisheries sector earn an average of Rp1,835,058 with 35 working hours per week.

In total, the labor force in Indonesia increased by 0.95 million to 154.0 million people. The number of unemployed people increased by 2.52% to 7.46 million people, with an open unemployment rate of 4.85%, up 0.09 percentage points compared to the February 2025 National Labor Force Survey data.

Why is productivity low?

The increase in the average net wages received by workers in Indonesia seems to reflect an increase in workers' welfare and promising economic prospects.

However, with worker productivity growth reaching 2.4% annually between 2005 and 2022, worker productivity levels in Indonesia only generated USD 15.6 per hour worked in added value to the national GDP.

The APO report diagnosis identifies five main causes of low productivity among Indonesian workers, which has been a trend since the first survey was conducted to examine the 2010-2020 period.

- The high proportion of informal employment, reaching nearly 60% of the workforce, with most working in low-skilled service sectors or agriculture with low added value;

- The shift of labor toward other service sectors and public services that are less productive and do not contribute significantly to the national GDP. Even though the number of service sector workers reaches 46% of the workforce, their productivity is below that of the manufacturing sector, given that high participation is not directed toward value-added service sectors such as technology and digital.

- Large companies (i.e., companies with revenues of at least USD500,000,000 per year) contribute only 14% of GDP, even though large companies are synonymous with the need for highly skilled workers and greater productivity.

- UMKM dominate UMKM provision UMKM 97% of jobs and contribute 57.2% to GDP, but not many of these companies are engaged in productive sectors. Increasing the productivity UMKM be a priority, but it would require a very long time and consistent guidance.

- An extreme declinein labor quality growth from 4.3% in the decade from 2010 to 2020 to -1.4% since 2020. In other words, productivity is not balanced with improvements in worker capacity and qualifications, which rank at the bottom of the APO index.

Three countries lesson

Reflecting on this situation, APO provides important strategic recommendations to be formulated in Indonesia's economic policy to boost productivity. First, increasetrade openness and integration with global supply chains by removing restrictions that hinder capital inflows and creating capital market efficiency.

Vietnam provides the best lesson on openness as the key to progress. Seriously following up on the Doi Moi measures in 1986, Vietnam's long-term economic strategy focuses on industrial restructuring and modernization towards development. Investor confidence, which has recovered along with the rise in the trade openness index, is reinforced by structural reforms of slow and unproductive state-owned enterprises.

Second, increase the new education budget by 3% of GDP. APO notes that even though education participation has improved, Indonesia still ranks 9th out of 21 in Future Workforce Preparedness and scores 57.7 in the Labor Market Index. Both indices underscore that strict labor regulations and low worker skills reduce investment attractiveness and limit the possibility of formal employment growth.

Malaysia is cited by the APO as an example of a successful education system, ranking fourth in terms of the largest allocation of education spending relative to GDP. The quality of primary and secondary education is a structural factor contributing to the increase in the number of skilled and highly productive workers in Malaysia. It is the success of the Malaysian education system that has made it possible to halt the decline in the quality of workers.

Third, with the increasing participation of labor in the service sector, the APO strongly recommends structural reforms for the service economy, by reducing restrictions and barriers to FDI in the service sector in order to catch up with the productivity of the manufacturing sector.

APO refers to Thailand's success in the third lesson. In the land of white elephants, the deepening of productive capital is increasingly focused on the digital sector and the adoption of AI technology. Jobs in the health and tourism sectors have successfully supported optimal growth after the agricultural and manufacturing sectors were simultaneously strengthened, despite the residual effects of the 1997 Asian Crisis that still leave their mark today.

"Despite these challenges, Indonesia's gross savings of 38.4% of GDP reflect a stable macroeconomic foundation that supports long-term investment. To maintain productivity growth, Indonesia must focus on reducing barriers to trade and investment, strengthening institutions, and addressing infrastructure constraints," the report concluded.