Minister of Finance Purbaya Yudhi Sadewa will take action against illegal imports of used clothing (balpres) with fines, a step awaited by textile industry players to restore their competitiveness. This policy aims to create a deterrent effect while protecting domestic production.

In Pasar Senen, Jakarta, thrift traders are starting to feel uneasy about the new regulations. "We're nervous, Mbak. If Purbaya is aggressive, our thrift will close," said Taufik (not his real name), one of the traders. However, Purbaya emphasized that Pasar Senen will not be closed, but will be 'filled' with domestic goods.

Data from the Directorate General of Customs and Excise (Kemenkeu) notes that from 2024 to August 2025, there have been 2,584 cases of illegal balpres enforcement, with a total of 12,808 packages of evidence worth IDR 49.44 billion. However, enforcement in the form of destruction alone is considered insufficient. "I spend money to destroy them, but the people are fed in prison," said Purbaya at the Ministry of Finance office on October 22.

But on the ground, the policy is causing anxiety. Taufik is not the only one worried. "If the expedition is fined, the stock will be even smaller, the price of bales will go up. It's already gone up a lot now," he complained. He sells imported used clothing from Japan and Korea, which is now increasingly difficult to obtain.

Although Purbaya emphasized that Pasar Senen would not be closed, in reality, according to Taufik, there is no adequate local substitute. "There is no thrift in Indonesia, Mbak. There are only knock-offs (imitations-read )," said Taufik, with a bitter laugh.

Purbaya's New Breakthrough

The government is no longer playing around in dealing with the flood of imported used clothing that is eroding the domestic textile industry. Minister of Finance Purbaya Yudhi Sadewa has emphasized that he will take firm action against illegal importers or balpres who have been freely entering markets in major cities, including Jakarta.

Purbaya said that this crackdown does not mean closing down trading activities in thrifting centers like Pasar Senen. On the contrary, he said that the area could actually transform into a space for legal and competitive local products.

"Pasar Senen will not be closed. Later, it can be filled with domestic goods," said Purbaya at the Ministry of Finance office, Jakarta, Wednesday (22/10/2025).

He emphasized that the government wants to protect legitimate UMKM actors who produce goods domestically, not to revive illegal supply chains that put pressure on local textile producers. "Our goal is not to revive illegal UMKM, but legal UMKM that can create employment and production in the country," he asserted.

As part of this firm step, Purbaya will implement a new rule in the form of fines for illegal used clothing importers, not just destruction of goods or imprisonment. He believes that the current enforcement mechanism actually makes the state lose twice: the domestic industry is under pressure, while state funds are drained to destroy confiscated goods and finance prisoners.

"So far, the goods have been destroyed, the perpetrators imprisoned, but the state gets nothing. Instead, it costs money. So we will change it later, we will fine them," he said.

Purbaya also claimed to have a list of names of balpres import players and promised to take firm action, including blacklisting them from import activities in the future. This step is part of the government's grand strategy to restore the national textile industry, which in recent years has been under pressure due to the overflow of cheap imported goods and soaring production costs.

The Impact of Import Restrictions on the TPT Industry

Textile business actors from upstream to downstream have long been complaining about the flood of imports. The Chairman of the Indonesian Textile Association (API), Jemmy Kartiwa Sastraatmadja, emphasized that the balpres issue is not just about used clothes.

According to him, this concerns the long chain of the interconnected TPT industry, absorbing millions of workers, and being one of the sectors with the longest and most complex economic chain in Indonesia.

"If imported ready-made clothing enters too easily, our workers will automatically have no sewing work. From tailors to fabric makers, from fabric to yarn, to fiber and filament yarn, everything is affected," he said when contacted by SUAR, Sunday (26/10).

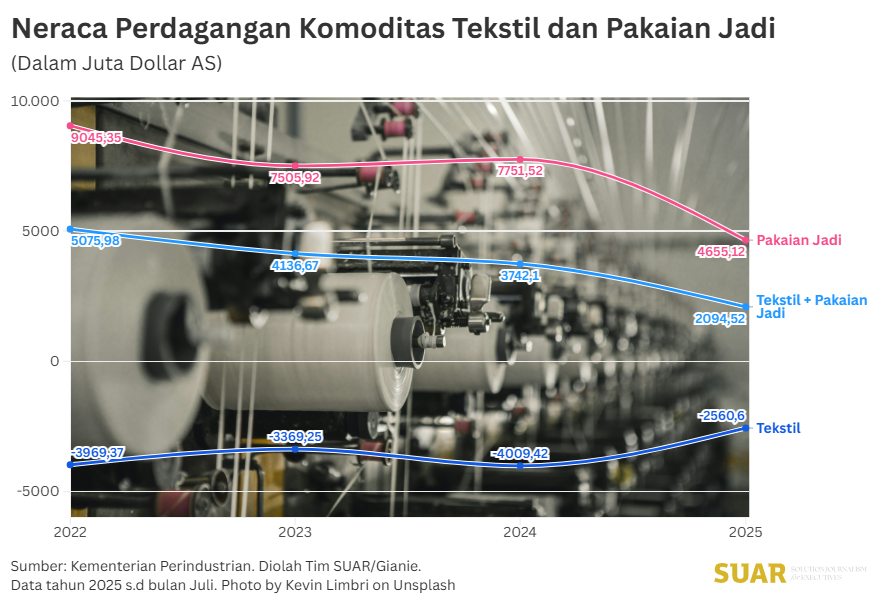

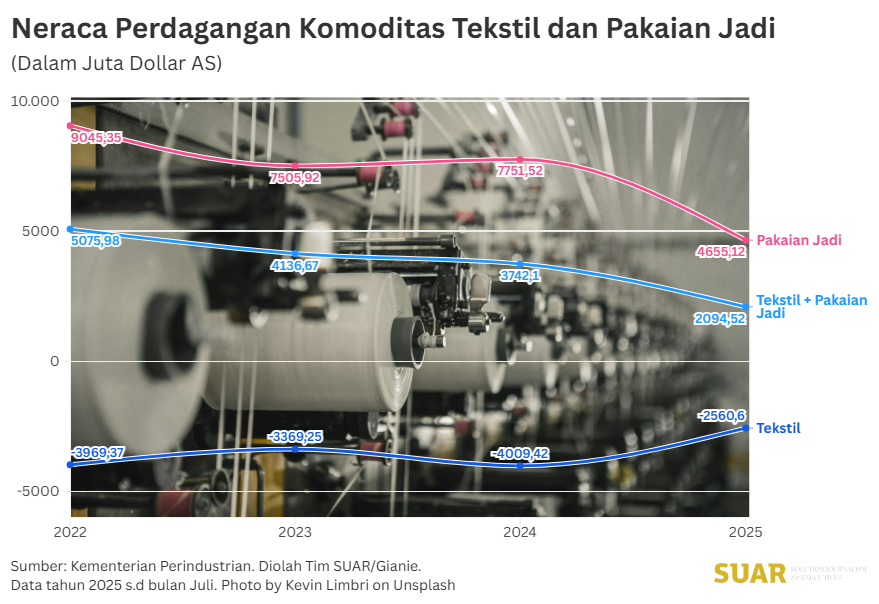

Based on data from the Ministry of Industry, as of August 2024, the TPT industry absorbed around 3.97 million workers or almost 20% of the total manufacturing workforce. However, since the pandemic, layoffs have spread, production capacity has decreased, and several companies have gone out of business.

The Chairman of the Indonesian Textile Association (Apsyfi), Redma Gita Wirawasta, noted that the import volume of yarn and fabric has jumped sharply since 2021. "For yarn, from 200 thousand tons in 2021 to 380 thousand tons in 2024. Fabric increased from 600 thousand tons to almost 1 million tons," he added.

According to Apsyfi's records, since 2022, this massive import has resulted in two large producers going bankrupt, while two others are only operating at 40 percent of capacity. Of the six remaining producers, the average utility has decreased to 70 percent. "Our association members alone have decreased from 23 companies in 2022 to 19 this year," he said.

The government is trying to respond through the Minister of Trade Regulation Number 17 of 2025 which tightens the import of textiles and textile products by requiring import approval documents. However, the regulation, which came into effect on August 29, 2025, has not been effective enough to restore the enthusiasm of the business world. The reason is that imported products have already flooded the domestic market, putting many small business actors under pressure to the point of bankruptcy.

Data from the Bandung Convection Entrepreneurs Association (IPKB) notes that around 40% of small and medium-sized convection industries have stopped operating since the Covid-19 pandemic. This situation is worsened by the weak supervision of import flows.

The government argues that most imported products are needed to meet the demand for raw materials in the downstream sector. But Redma emphasized that this argument is not entirely true. "The industry here can actually produce. It's just that, once dumping goods enter, they lose price competition. The difference can be up to 40 percent," he said.

From Prohibition to Non-Tariff Barrier

Through the Minister of Trade Regulation (Permendag) Number 17 of 2025, the government is tightening the flow of imported textile products and ready-made clothing by requiring import permits under the Prohibition and Restriction (Lartas) scheme. The Ministry of Industry complements this regulation with Permenperin 27/2025, which regulates the requirements for producers and importers so that the flow of incoming products is more controlled.

Jemmy assesses that this step is a healthy non-tariff barrier. "In the past, imports of ready-made clothing could enter freely. Now it must go through permits from the Ministry of Industry and Trade. The positive impact may only be felt in the first or second quarter of 2026, but at least there is hope," he said.

Including the addition of fines, for Jemmy, this policy is another form of trade barrier that is indeed needed. "The name of trade barrier is various. One of them is sanctions. I think the idea of giving fines is good, considering Indonesia's coastline is very long. If there is no deterrent effect, the flow of illegal goods will continue to enter," he said.

The flood of imported goods, including used clothing, makes the local industry lose its competitiveness. On the other hand, many countries are now strengthening their domestic markets, after the era of free-tariff globalization that is starting to be abandoned. "Now many countries are competing to protect their own industries. Indonesia must also move in that direction," he said.

In this case, Jemmy also acknowledged that weakening public purchasing power has increased demand for cheap goods. "If people don't have money, what can they spend? When purchasing power falls, they will choose the cheapest. So the main solution is not just enforcement, but how to create jobs so that purchasing power increases."

Jemmy emphasized that job creation is the root of all problems. "If the industry can increase utility, it will automatically absorb labor. When people work, they get paid and can spend their money. Purchasing power increases, the economy moves along," he said. Therefore, according to him, affirmative policies towards local producers need to focus on job creation, not just price subsidies.

Read also:

Besides holding back the flow of imports, the local textile industry faces serious challenges in production and energy. Under the Indonesia-European Union Comprehensive Economic Partnership Agreement (IEU-CEPA), textile products can only enjoy a zero percent tariff to Europe if they are produced with environmentally friendly energy.

"This means exports must meet green energy standards," Jemmy explained. He emphasized that the government needs real support, such as providing clean energy and gas pipeline infrastructure to industrial centers, especially Greater Bandung and Greater Solo. Without this, the competitiveness of the industry in the European market will be threatened.

Green energy requirements are not just environmental demands, but also about cost efficiency and attracting global investors. "The government must accelerate these facilities. This is not just about exports, but the future of the national textile industry," he said.

Fines, Laws, and Enforcement Integrity

On the other hand, the Chairman of the Indonesian Garment and Textile Association (AGTi), who is also the Vice President Director of PT. Pan Brothers Tbk, Anne Patricia Sutanto, believes that adding sanctions will only be effective if accompanied by strict supervision in the field.

According to Anne, the main issue actually lies in the aspect of supervision: how can these illegal goods enter. "The import of used clothing is clearly prohibited by the Regulation of the Minister of Trade. So the problem is not just about being fined, but why can it enter," she said via telephone to SUAR, Sunday (26/10).

Anne, who is also the Head of Trade at the Indonesian Employers' Association (Apindo), believes that the government needs to strengthen supervision at vulnerable points, especially small ports and unofficial sea routes.

"These goods often enter through small ports that are not guarded by customs officials. So there needs to be synergy between agencies, the TNI, Polri, Customs, the Ministry of Home Affairs, the Ministry of Trade, and the Ministry of Industry, to close that gap," she said.

For Anne, adding sanctions in the form of fines is only relevant for goods that have already entered the market. "If it has reached small traders, it may be better to fine them than to burn the goods as before. But for those at the level of large importers, they should not be able to get through at all," she asserted.

She proposed a two-way mechanism: for small traders who confess and are willing to reveal the origin of their goods, a simple administrative fine is sufficient; but for those who are dishonest and admit their violations, they still need to be processed legally according to the prevailing provisions in the Criminal Code.

"If a violating trader does not admit the source of the illegal goods, it means there is an intention to conceal the violation. That fulfills the requirements of a buyer not acting in good faith and must be processed. Because in the Criminal Code it is clear that if a buyer knows the goods are illegal but still buys them, the buyer can be subject to the article on participating in the crime," she said.

For industry players, supervision and the integrity of law enforcement officials are key. "Regulations already exist, but if enforcement in the field is not firm, it's useless. The leaks need to be mapped, which ports, who is involved. If all parties have integrity, I am sure it can be resolved," said Anne.

Anne's statement is in line with Purbaya's plan to blacklist rogue importers so they can no longer transact. But without a strong distribution chain tracking system, this policy has the potential to become just a slogan on paper.

The Long Road to Industry Recovery

The government hopes that the control of balpres will provide space for legal local products, but the challenges remain significant. Jemmy emphasized job creation as the root of the problem: "If the industry can increase capacity, it will automatically absorb labor. When people work, purchasing power increases, and the economy moves."

According to Eko Listyanto, an economist at INDEF, this policy is a good first step. "This control prevents price wars that harm local industry. But it needs to be followed up with a long-term strategy, such as reducing dependence on imported raw materials and strengthening the upstream industry," he told SUAR via written statement, Sunday (26/10).

Eko also emphasized the importance of socialization and enforcement of sanctions so that UMKM do not become victims. "If the goods being sold are illegal, then there needs to be socialization and enforcement of sanctions so that UMKM sell products that are permitted by the government," he said.

With a combination of regulations, sanctions, supervision, and support for local production, the textile industry is expected to recover, absorb labor, and become competitive again, while also providing alternatives for people who have been dependent on imported products.