Cooperatives have long flourished in Indonesia. It is the pillar of the community's economy, but it is in danger of being outdated. In Singapore, cooperatives are winning.

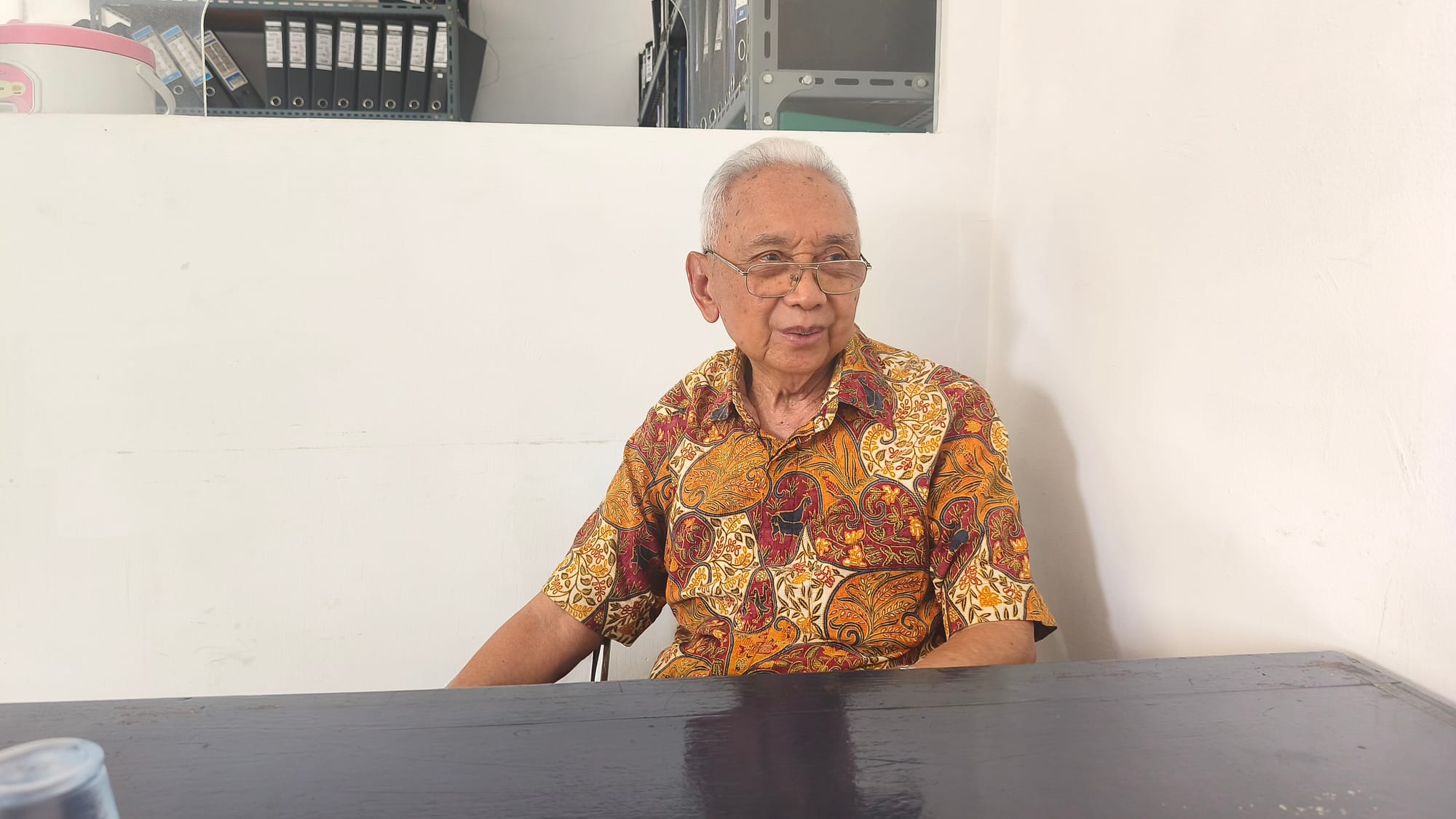

Achmad Saubari Prasodjo had just returned from the mosque after performing zuhur prayer on Thursday, July 24, 2025 when SUAR met him. Entering his office, a 3-story building in the Jati Padang area, Pasar Minggu, South Jakarta he immediately sat at his desk.

For almost half a century Achmad Saubari has had an office here, a cooperative that sells a wide variety of merchandise. From snacks, canned and bottled drinks, to medicines, to frozen meat.

While sipping coffee in a tumbler, the 85-year-old man recalls how the Sejati Mulia Cooperative was first established, back in 1978. At that time, several residents living in Jati Padang Village agreed to form a small business institution.

"It all started with the awareness to help each other," says Achmad. The founders of the cooperative come from diverse backgrounds, ranging from civil servants, private sector, to small entrepreneurs. Mutual cooperation is the main foundation.

The first office of the Sejati Mulia Cooperative was in a wooden hut that used to be the project post for the construction of the complex. The building was used by contractors to arrange building materials before the complex was built. In fact, the building was also used by the village administration. From that small and simple place, the Sejati Mulya Cooperative began to grow.

The first office of the Sejati Mulia Cooperative was in a wooden hut that used to be the post of the complex construction project.

Initially, the cooperative's business line was only savings and loan services between members and traders around the cooperative's location. Usually, vegetable traders came to the cooperative to apply for loans in the morning. They would repay the loan according to the promise agreed upon with the cooperative. "If their merchandise sells well, the loan can be paid off in the afternoon," said Achmad.

Although the turnover of money is not jumbo, this model is very effective in encouraging the development of cooperatives. The decade of the 1990s was a pivotal point for Sejati Mulya Cooperative.

As profits improved, the cooperative bought a building owned by the Ministry of Agriculture through a bank loan. The house was quite large and was immediately used as the cooperative's office until now. "Now, the BCA and BRI bank buildings next to this office belong to the cooperative. They rent it to us," said Achmad.

Once triumphant in its time

Currently, Sejati Mulia Cooperative has 3 lines of business. First, savings and loans, still the same as when the cooperative was first established.

Second, rent the building, room, and land. The room on the second floor of the cooperative is rented out to anyone who wants to rent it. Land in the cooperative parking lot is also rented out to street vendors. Third, shops.

The cooperative-owned shop sells goods from two sources. Member-made cakes and chips are displayed on the same shelves as goods from suppliers. This mix gives the cooperative store its own color.

Achmad does not deny that in terms of price and product variety, cooperatives cannot compete with large retailers, such as Alfamart, Indomaret, and Family Mart, which are not far from cooperatives. Even so, this does not mean that cooperatives will lose the competition. Achmad emphasized the importance of members' awareness to shop at cooperative stores. "We have to shop here, it's ours together. The benefits will also come back to us," he said.

"We have to shop here, it's ours together. The profit will also come back to us,"

The number of members is now around 2,400, spread across Jati Padang, Pasar Minggu, and some retirees who have moved. The entrance fee was raised from ten thousand to thirty thousand, in line with the growth of the cooperative's business and facilities.

The organizational structure of the cooperative board consists of a chairperson, treasurer, and business unit manager. Meanwhile, the savings and loan, shop, and rental business units are managed by the board. Daily decisions are discussed weekly, while major policies are determined at the Annual Members Meeting (AGM). At the RAT, the amount of the remaining operating result (SHU) is also decided to be distributed to all cooperative members.

Eroded by the times

In 2017, the Sejati Mulia Cooperative reached its heyday. At that time, the net profit for the year reached Rp1.7 billion. Because of the large profits, coupled with a loan from the bank, the cooperative dared to buy the building across the street, which is currently rented out to an electronic goods store. Later, the rental proceeds from the building will be rotated again for other business units.

Unfortunately, this did not happen. The pandemic disrupted all the plans that the cooperative management had made. "Income has plummeted. Until now, our debt to the bank has not been paid off," said Achmad.

The pandemic disrupted all the plans that the cooperative board had made.

Even so, Achmad claims that none of the cooperative employees have been fired. Although salaries were reduced, Achmad ensured that all cooperative employees still received their rights.

Until now, Achmad said that the cooperative's economy has not yet recovered. In addition to the debt that has not been paid off, since 2022, the cooperative has never again distributed SHU to members. Even though it is the moment that members are most waiting for. "The cooperative is still losing money to this day, not to mention our installments and operations," said Achmad.

So, one of the most sensible steps to save the cooperative was to sell the leased building. Achmad asked all administrators and members to offer the building. The price was pegged at 11 billion.

Despite the shaky progress, Achmad still believes the cooperative he leads will survive. "Fortune can come from anywhere," he said. Most importantly, the cooperative must be managed honestly and orderly.

Despite the shaky progress, Achmad still believes that the cooperative he leads will survive.

Achmad firmly rejects the practice of borrowing and lending without procedures, especially if there are administrators who do it on the basis of having a position in the cooperative.

At his age, Achmad hopes that the cooperative management will undergo regeneration. He has been the head of the cooperative for more than one period. It is time for the management of this 47-year-old cooperative to be filled by an easier generation. "It's a shame but not many of the younger generation have the courage to take on this responsibility," he says.

Member-owned savings and loan cooperative

Similar to the story of the Sejati Mulia Cooperative in Jati Padang, Bina Sejahtera Cooperative was also established in 1978 and continues to operate to this day.

It all started with a small social gathering held regularly by migrants from Gunungkidul, Yogyakarta. They were civil servants, market employees, and self-employed workers who helped each other save money. From the arisan meetings, the idea to form a cooperative emerged.

After two years of existence, in 1980, the cooperative was officially incorporated. The 18 founders were almost all Gunungkidul residents who had lived in Cipinang Melayu for a long time. When the cooperative was first established, it did not have its own premises. The administrators hitchhiked from one place to another, ranging from schools to community meeting rooms.

The land and building were initially recorded as grants. But upon inspection, it turned out that all purchases were made with official receipts. The board then decided to apply for a certificate in the name of the cooperative. They did not want to leave problems for their children and grandchildren.

In the past, this cooperative was once victorious. Its membership had reached 647 people, spread across various housing estates around Cipinang Melayu. "We never delete the member number, even though the person has passed away," says Sulistiono, who manages the credit section of the cooperative. They come from various backgrounds and actively participate in cooperative activities. Today, there are only 57 active members.

The main activity of cooperatives since their inception has been savings and loans. Money collected from members was lent back for various purposes, from daily needs to small business capital. In addition, the cooperative used to manage public telephone services and daily credit for traders.

In the 1990s, they collaborated with the tofu-tempe production association, and opened a grocery store. "At that time there was no Indomaret, we were the most crowded," said Sri Sulastri, Chairman of Bina Sejahtera Cooperative.

The shop was a mainstay of the neighborhood before minimarkets began to mushroom. Sugar, flour, oil, all taken from the tofu-tempeh association were sold at affordable prices.

The shop was a mainstay of the local residents before minimarkets began to mushroom.

But that glory slowly faded. Supermarkets and retail stores began to set up one after another around the complex. The cooperative store slowly lost customers and revenue dropped dramatically. "We tried to manage it ourselves, but it was a loss," said Sutrisno, who takes care of the cooperative's bookkeeping.

Finally, Sulistiono said the management of the store returned to the old pattern: 60% managed by outsiders, 40% owned by the cooperative.

The cooperative survives through a strict savings and loan system. The maximum loan amount is limited to three times the total principal, mandatory, and voluntary savings. The rule is made so that the cooperative's money remains safe and can be rotated. "If the savings are five hundred thousand, then the maximum loan is one and a half million," said Sri Sulastri.

Unfortunately, not all loans are repaid. Some members defaulted on their loans because they lost their jobs, moved rent, and some were even addicted to online gambling. "There was even one who couldn't pay and said 'let's kill me', what else can I do? It makes it even harder to collect," Sulistiono said with a laugh.

To avoid such problems, the cooperative now only accepts members who live permanently in the Cipinang Melayu area. Residents who rent are not allowed to become members. The management does not want to take the risk that members run away and cannot be found.

Although there are many stories of failure, this cooperative also has success stories. Some home builders have borrowed up to hundreds of millions and repaid their loans on time. "We see who is diligent in depositing and smooth. That's the capital," said Sri Sulastri. Trust is the main thing they hold on to.

2020 was the toughest year in the cooperative's history. A massive flood submerged the shop and destroyed most of the merchandise. "The last one was a loss of Rp70 million," Sri Sulastri recalls. The refrigerator floated away. The office was a mess.

The impact of the floods had not yet fully recovered, and the pandemic came. Cooperative activities stopped, the shop became even quieter, and the annual meeting had to be postponed. The SHU for 2024 was only Rp26 million and went straight into each member's savings book. "It was divided, but not in cash. It just goes into the book because the amount is very small," said Sutrisno.

Hindered by regeneration

Today, the cooperative is managed by seven administrators. None of them work full-time. They only receive a small monthly honorarium. The credit and bookkeeping department gets Rp500,000 per month. Meanwhile, other administrators, including the chairperson, only receive Rp300,000 per month.

The honorarium was far below the minimum wage. But no one protested. They feel this is a form of responsibility, not a job. "We are just volunteers, walking from home to the office, sometimes even spending our own money," says A, minute 15:32.

The majority of the board is elderly. The age of the board members is above 65 years old. But they still come to the cooperative office as scheduled, and serve members who are still active.

Sri Sulastri said that regeneration is an internal problem that never ends. Every time it is offered, young people are reluctant to become administrators. They are not interested in small salaries and voluntary work. "If offered Rp300,000, who would want it?" she said.

In fact, this cooperative was built on the spirit of kinship. In the past, anyone who needed money to build a house, get married, or send their children to school would come to the cooperative. "People here used to look for almost everything they needed at the cooperative," Sulistiono said. Not to mention that nowadays people are more familiar and use online loans rather than coming to the cooperative.

In the past, anyone who needed money to build a house, get married, or send their children to school would come to the cooperative.

The administrators admitted that they were disappointed with the government's attitude. They feel that they have never received support, either in the form of training, incentives, or capital strengthening. Even the kelurahan rarely attends annual meetings. "The village head is supposed to be the protector of the cooperative. But they never come," said Sulistiono.

The cooperative once hoped for state intervention, especially after suffering losses due to floods and the pandemic. But help never came. "At best, we were only given clothes for the cooperative's anniversary," Sulistiono says with a laugh. Even when they attend training or meetings, the results are not sustainable.

In the midst of this disappointment, a new program emerged called Koperasi Merah Putih. The government initiated one village cooperative, complete with loan capital through banks.

Bina Sejahtera management responded that the program was only good on paper. Without good supervision, cooperatives can become a tool of manipulation and a field of corruption. Especially if run by people who are not sincere. "If the management is not sincere, it won't work," said Sri Sulastri.

The officers reminded us that building a cooperative is not the same as setting up a shop. It takes time, commitment, and trust built over many years. "In our village, there was once a cooperative made by the government. But it went bankrupt," said Sulistiono.

Labor resistance tool

While many cooperatives struggle in this day and age, cooperatives in neighboring countries still exist and have even become big players in their regions. Like the National Trade Union Congress (NTUC), which runs consumer cooperatives that are now giant supermarket chains, it started with a simple mission: to provide affordable prices for workers.

Today, they dominate the retail market and set aside a portion of their profits for education and member welfare.

NTUC makes the list of the 300 largest cooperatives in the world. NTUC has sub-cooperatives, namely NTUC Fair Price and NTUC Income. Both are engaged in the retail and insurance sectors respectively. Currently, there are more than 500,000 cooperative members who are also owners of their businesses.

NTUC Fair Price already has more than 291 chain stores spread across various parts of Singapore. They range from convenience stores that provide daily necessities, to supermarkets and hypermarkets.

Although Fair Price labels its outlets with various names, they are all under the NTUC Fair Price. The mechanism applied in NTUC is a joint cooperative. Where all members have the right to determine the policies of the company with equal voting rights.

Each member is given the opportunity to express their opinion on the company at the Annual Members Meeting (RAT). In addition to discussing policies, the RAT will also discuss the remaining results of operations (SHU) and its distribution.

Interestingly, in the SHU distribution, the size of the SHU received will be based on the number of member transactions at the Fair Price convenience store. In other words, members who shop more, will get a bigger SHU.

Members who spend more will get more SHU.

The cooperative's history dates back to 1973, when Singapore's national labor union, NTUC, initiated the establishment of a retail cooperative to respond to the public's unrest over soaring inflation. At that time, prices of basic necessities rose sharply and the common man felt a direct squeeze on their kitchens.

Thus was born NTUC Welcome, the forerunner of FairPrice, with a simple but ambitious mission: to ensure that anyone, from any walk of life, could access basic goods at fair prices.

From a single cooperative store, FairPrice slowly grew into a retail giant. But it never lost sight of its social roots. Today, FairPrice manages more than 570 stores across Singapore, ranging from regular supermarkets, premium outlets, hypermarkets to 24-hour convenience stores.

It has also expanded its food business line through NTUC Foodfare and Kopitiam, affirming its commitment to providing end-to-end solutions for citizens' daily needs.

Profit back to the community

What keeps FairPrice relevant and loved by the public is not just the vast network of stores or the practicality of the service, but the cooperative principles they uphold. Profits are not distributed to a handful of shareholders as is common in private companies, but are instead returned to the community.

FairPrice's proceeds are used to support various social programs, including contributions to the Singapore Labour Foundation and the Central Co-operative Fund. In this way, FairPrice demonstrates that companies can remain competitive without sacrificing their social conscience.

When the Covid-19 pandemic hit, FairPrice not only kept prices stable, but also changed the way they served. They launched the FairPrice on Wheels service, where mobile trucks bring staples directly to residential areas that are difficult to access or inhabited by vulnerable groups, such as the elderly. In a crisis situation, their presence is not just felt as a store, but as a caring neighbor.

FairPrice's social mission is also reflected in its special discount program for the elderly and price subsidies for essential items. While other retailers race to provide discounts to increase sales volume, FairPrice utilizes discounts as a form of economic intervention for the neediest.

FairPrice's social mission is also reflected in its special discount program for the elderly and price subsidies for essential items.

But that doesn't mean the road has always been smooth. FairPrice has also been criticized for pricing certain products higher than competitors. On social media, some consumers questioned the cooperative's commitment to affordable prices.

The management responded openly, explaining that they prioritize quality, stability of supply, and long-term partnerships with local producers. They prefer not to play in price wars that could pressure small farmers or suppliers.

In addition, challenges from global e-commerce and heavy discounting from new players were real pressures. But instead of going against the grain, FairPrice chose to transform. They strengthened online services, developed a user-friendly online shopping system, and integrated the LinkPoints loyalty program to provide added value for consumers.

When it comes to the environment and sustainability, FairPrice also shows its concern. They actively run single-use plastic reduction programs, consumer education on healthy lifestyles, and measurable food waste management. Not all of these are immediately visible when one walks the aisles of their stores, but the impact is felt systemically.

Preparing to go global

FairPrice also realized that resilience cannot only be built domestically. Therefore, they started exploring cross-country collaborations. One example is their collaboration in Vietnam, which gave birth to Co.opXtra Plus, a hypermarket model that combines a modern approach with a cooperative spirit. This expansion not only broadens their network, but also spreads the idea that cooperatives can succeed on the international stage.

In an increasingly competitive and capitalistic world, FairPrice is a reminder that retail doesn't have to be cold and efficient. It can have a friendly face, a caring heart, and a purpose bigger than just profit margins.

FairPrice proves that cooperatives are not an old, outdated model, but an economic system that is still very relevant-especially when people need fairness, solidarity, and equal access.

The story of FairPrice is not just about the goods sold on the shelves. It is a story of how a nation safeguards the worth and dignity of its people. In every shopping trolley pushed at FairPrice outlets, there is a long narrative of social struggle, the courage to innovate, and a commitment to shared prosperity. S

Mukhlison, Rohman Wiboro and Harits Arrazie