The latest developments in poverty figures reflect a paradoxical phenomenon between poverty in cities and villages. The general assumption is that poverty in villages is increasing, causing people to go to cities. However, now it is the opposite: the poverty rate in villages is decreasing and poverty in cities is increasing.

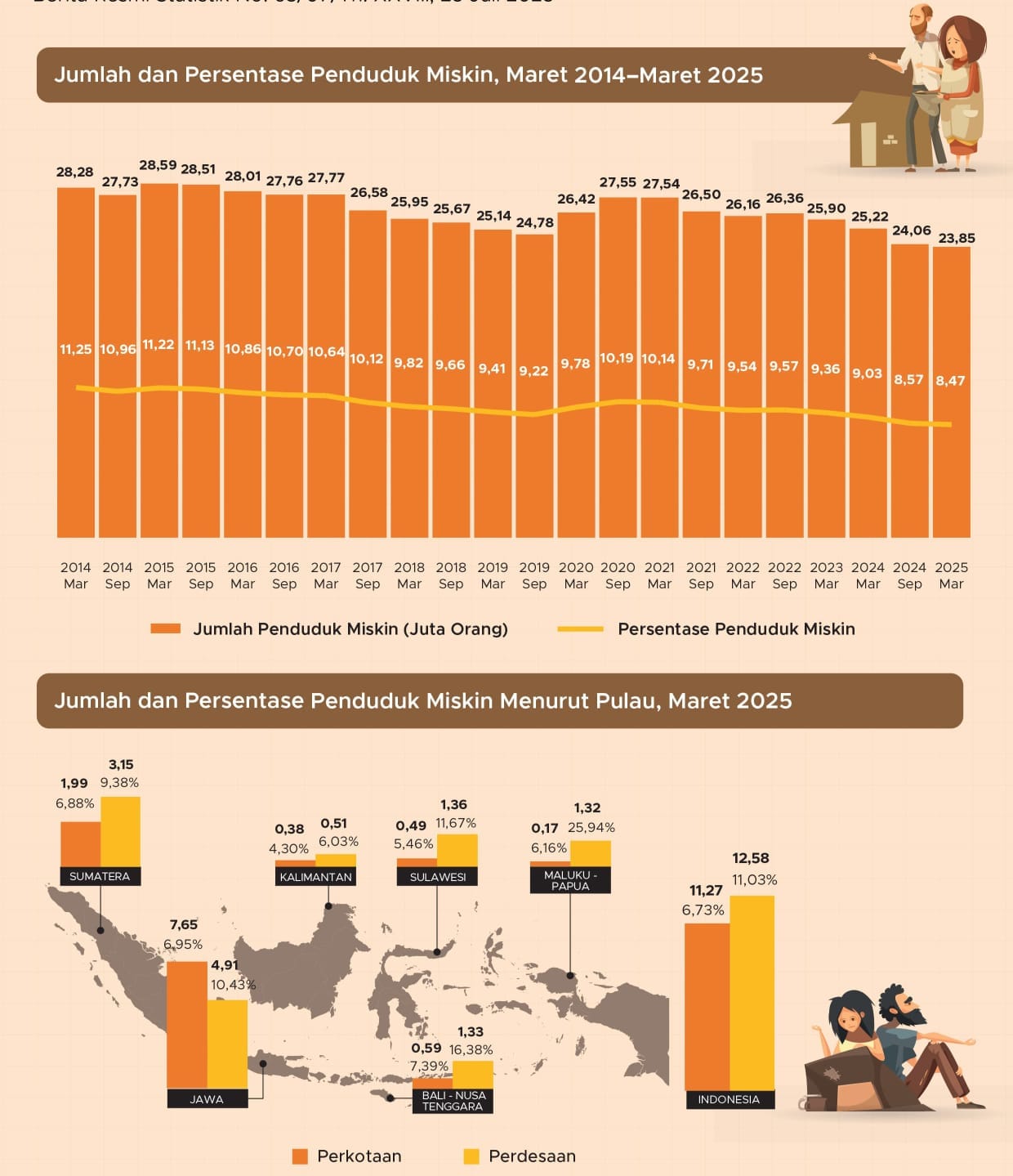

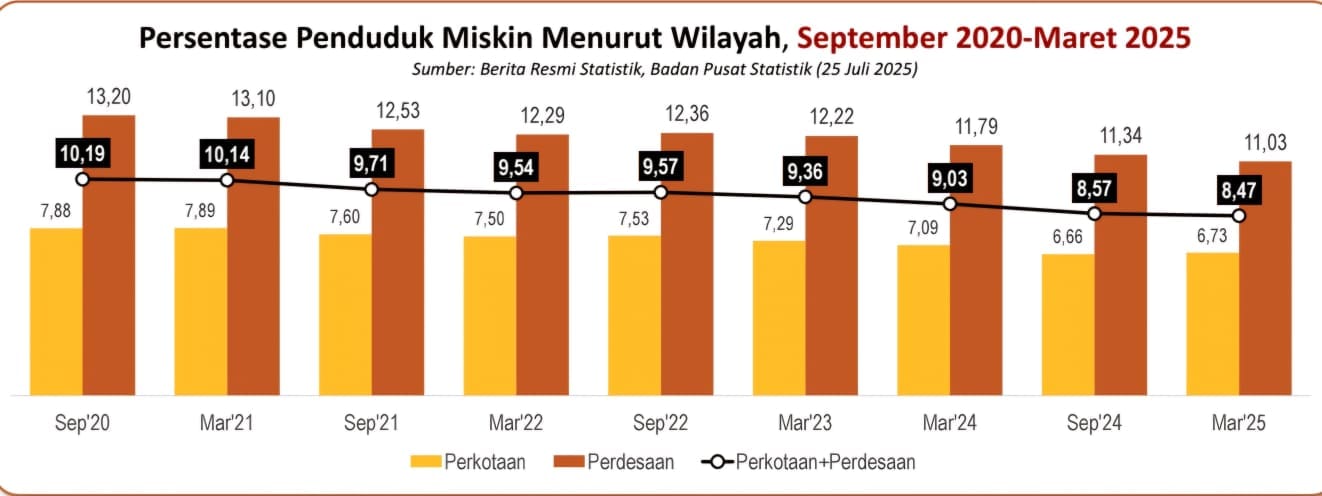

The Central Statistics Agency (BPS), which finally released poverty figures for March 2025 on Friday (25/7/2025), stated that the total percentage of Indonesia's poor population as of March 2025 was recorded to have fallen to 8.47%. This figure is down slightly by 0.1 percent compared to September 2024. This is the lowest figure in the last two decades.

Deputy for Social Statistics at BPS, Ateng Hartono, in a press conference on Friday (25/7/2025), announced that the number of poor people fell slightly, by only around 200,000 people, to 23.85 million people, or 8.47% of the total population.

Although it only fell 0.1 percentage points from September 2024, this figure is recorded as the lowest poverty rate in the last two decades. "This is good news, even though it is small, because it still shows a consistent downward trend," said Ateng Hartono.

Different in villages, different in cities

However, behind the national figures, there are two contrasting stories: optimism in the villages, and an alarm that needs to be watched out for in the cities.

In the villages, good news comes through data: the poverty rate has fallen more sharply, from 11.34% in September 2024 to 11.03% in March 2025. Meanwhile, in cities, poverty has actually increased slightly, from 6.66% in September 2024 to 6.73% in March 2024.

"Poverty in rural areas is still higher than in urban areas, but income inequality in urban areas is higher: the urban Gini ratio is 0.395, while the rural Gini ratio is 0.299," said Ateng.

The Gini ratio is an index that describes income inequality with a range of 0 to 1. An index position close to 0 indicates that welfare is evenly distributed, while a figure of 1 indicates high inequality.

This difference is not just about statistics. What makes villages more resilient, and what makes cities more vulnerable?

Ateng explained that the driving factor behind the declining village poverty rate is the increase in the farmer exchange rate (NTP) as one of the keys. The NTP figure in March 2025 reached 123.72. The NTP position in March 2025 is higher than the last time the poverty figure was released, namely the NTP in September 2024, which was 120.30. This means that the selling price of agricultural products is higher than the production and consumption costs of farmers. Purchasing power increases, and poverty decreases.

In addition, the number of workers in the agricultural and trade sectors has also increased. In villages, these sectors are still the backbone, not just a last resort. When harvest prices improve, income increases, and more families can cross the poverty line.

Behind that, there is a fact that is often forgotten: villages are not just "poor areas" that passively wait for assistance. Many villages carry out local innovations, from farmer cooperatives, savings and loans, to tourism village programs that drive the economy. The decline in poverty that occurs, although slowly, is not only the result of government intervention, but also the initiatives of residents who are trying to survive in the midst of challenges.

Conversely, in cities, a slight increase is a signal that cannot be ignored. Even though the numbers look small, the impact is real for millions of people who live almost below the poverty line.

Ateng explained that there are two major pressures: rising food prices and an increase in underemployment, people who have jobs, but their working hours are short or their income is not sufficient. "In urban areas, the number of underemployed people increased by 0.46 million in February 2025 compared to August 2024," he said.

BPS data shows that the number of underemployed people increased by around 460,000 people. Meanwhile, the prices of several important commodities, such as cayenne pepper, cooking oil and onions, continue to soar.

For poor urban residents who live on daily wages, a difference of one to two thousand rupiah per kilogram is not a small number. That could mean one less meal to eat. "The increase in the price of a number of food commodities, such as cayenne pepper, cooking oil and garlic," said Ateng.

Cities also have a deeper problem: inequality. The Gini ratio in urban areas reaches 0.395, far higher than in villages, which is only 0.299. The source is clear: income variation in cities is much wider. There is a small group with very high incomes; while below them, the majority of informal workers struggle to maintain uncertain incomes.

"Poverty is indeed higher in villages than in cities, but inequality is higher in cities," he said.

There is also the issue of extreme poverty, which was reported at 0.85% this year. At first glance, this appears to be an increase compared to last year's 0.83 percent. However, this is not an actual increase. Ateng Hartono explained that BPS uses a new method: not only using PPP (Purchasing Power Parity) USD 1.9 (2011), but now using PPP USD 2.15 (2017) and adding a spatial deflator to better suit regional conditions.

If calculated with the new method last year, the figure would have been 1.26 percent. This means that extreme poverty has actually decreased.

Learning from successful urban UMKM: Nasrafa's story

Amidst the fluctuating economy and the heavy challenges of doing business in a big city, Yani Nasrafa's story can serve as an example of how UMKM can survive and even grow. The owner of the Nasrafa batik business believes that the most important step is to consistently maintain product quality and continue to innovate.

"Continue to consistently innovate with quality products, manage solid human resources, and seek potential markets abroad," said Yani.

In addition, she is also active in opening networks to various lines. For the export market, Yani directly contacts Indonesian trade representatives abroad, such as the Indonesian Trade Promotion Center (ITPC), Trade Attachés, and the Indonesian Embassy. Meanwhile, domestically, she approaches organizations such as the Indonesian Doctors Association, the Indonesian Notaries Association, lecturers, officials, artists, and other professionals who match Nasrafa's target market.

According to Yani, the success of UMKM is also inseparable from the support of many parties. Assistance from related agencies and ministries, banking institutions, and organizations such as KADIN, all play an important role. This collaboration helps overcome common obstacles for urban UMKM, such as access to capital, promotion, and market expansion.

However, she emphasized the importance of training that is not just a formality. "The training must be continuous and measurable, not just occasional or to spend the budget," said Yani.

For her, it is also important to have a separation of classes or segmentation of business actors, so that the training materials, curriculum, and instructors are appropriate to the needs. "If the class is A, then the teacher must also be A, the curriculum is A, and the facilities must also be supportive," she added.

Nasrafa's experience shows that the progress of urban UMKM is not only about the hard work of the business actors themselves, but also about the right and sustainable support. Amidst urban poverty data that is sometimes not fully recorded, stories like Nasrafa's prove that solutions still exist, provided there is synergy between business actors, the government, and the supporting ecosystem.

Poverty is not just numbers on paper

Behind the good news of the decline in national poverty, Executive Director of the Center of Economic and Law Studies (CELIOS) Bhima Yudhistira reminds us of a fundamental problem that needs to be addressed immediately.

According to him, this figure is not enough to capture the reality on the ground. He assesses that the BPS poverty calculation approach, which is almost five decades old, is too narrow and no longer relevant to the economic realities and consumption patterns of today's society.

Therefore, although statistically there is a decrease, the impact on policy and public welfare is still not felt significantly. "The poverty figures with this old method will never truly answer the reality on the ground," said Bhima.

Instead of just looking at how much we spend, Bhima suggests that BPS also look at welfare from how much we can actually set aside after paying for all basic needs.

Furthermore, the gap between official government data and international agency data is increasingly revealing: the World Bank estimates that around 68.2% of Indonesia's population lives below the international poverty line, a figure far greater than BPS records.

In urban areas, the challenges are increasingly complex. Rapid urbanization, the shift of young generations to cities, and the increase in the cost of living that is moving faster than wages, cause many city residents to fall into new poverty. According to CELIOS, many of them live in rented houses or boarding houses, which are not administratively recorded in the Integrated Social Welfare Data (DTKS).

CELIOS research says that poverty reduction efforts, especially in cities, require concrete steps that directly touch the community. One thing that can be strengthened is short-term social assistance programs such as electricity discounts, public transportation subsidies, and scholarships for children from underprivileged families.

In the long term, he also suggests housing and rental subsidies for vulnerable groups in cities. The reason is that the cost of housing is one of the heaviest burdens for urban poor people, which is often not recorded in official data.

In addition, CELIOS emphasizes the importance of involving local communities, such as RT, RW, cooperatives, and community organizations, as the spearhead for collecting data and distributing assistance.

Nevertheless, CELIOS highlights the obstacle that many policies and programs are still very centralized in the hands of the central government. This narrows the space for innovation at the village, sub-district, city and village levels. According to him, a review of the technical guidelines and instructions is needed so that local governments can be more flexible in innovating according to the needs of their respective regions.

Furthermore, he also sees the potential of cooperatives in the city as a solution to reduce the cost of living, stabilize the prices of staple foods, and open access to low- or no-interest financing. However, many cooperatives are instead in a state of suspended animation due to minimal support and incentives.

Urban farming is also considered a promising opportunity, not only in big cities but also in suburban areas close to rural regions. However, challenges remain: infrastructure, supply chains, and the limited availability of affordable business land are still major obstacles. Not to mention classic problems such as expensive rental costs and thuggery that often occur in many cities in Indonesia.